Mustelids exemplify ingenuity.

These mammals form a diverse and far-flung family, ranging from tiny country weasels to tundra-traversing wolverines. They are tenacious, ferocious, and startlingly clever. From tool use to burrowing to cooperating with other species, Mustelids remind us of the power of persistence and audacity.

Honey Badgers: Brains, Brawn, and Bravado

“And a taste of honey is worse than none at all.”

– Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, I Second That Emotion

The subject of this section would agree. Despite weighing only around 25 pounds, honey badgers have been filmed muscling lions away from carcasses. A honey badger staring down a full-grown lion (or lioness) is comical, even endearing. Watching one attempt to intimidate an entire pride is delightful, but this little fellow is more than compact courage.

Zimbabwe’s Shona people tell stories of honey badgers outwitting hyenas and stealing fire from the gods. According to them, a honey badger won a digging contest with Death itself by burrowing so deep that Death lost track of him.

Like many myths, this one is not baseless. Stoffel, an irrepressible rescue, is a testament to their resourcefulness.

Raised by a farmer from infancy, Stoffel was brought to the Moholoholo Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre because safe release was impossible. His antics, featured in documentaries like Honey Badgers: Masters of Mayhem and The Mighty Weasel, have frustrated and confounded his keepers for years. Though we may have some sympathy for them, their Sisyphean nightmare is quality entertainment for the rest of us.

Every time his keepers thought they’d finally built an escape-proof enclosure, their little captive has proved them wrong. So far Stoffel has:

- Stacked rocks and logs to climb over walls

- Used a rake as a ladder

- Rolled tires against fences to create stepping stones

- Learned to unlock several kinds of gate latches

- Dug elaborate tunnels when he couldn’t climb out

- Trained his female companion to crouch down so he could use her as a stepladder (true love, mustelid style)

- Thrown mud balls at electric fences until they short-circuited

- Built tools from sticks and stones to reach high places

And while their brains and bravado serve them well, honey badgers have no qualms with falling back on their physical attributes.

Their hides are like baggy jackets. If grabbed from behind, they can swivel to deliver a nasty bite. They are also resilient against snake venom, with reports of individuals sleeping off cobra bites. They’re also said to run backward as confidently as forward.

Do they look odd moving backwards? Maybe.

Do they care? No.

HBs and the Honeyguide: A Contested Relationship

Do our fearless friends follow Honeyguide birds to honey?

Maybe.

A 2023 study in the Journal of Zoology reviewed existing evidence and conducted 394 interviews with honey-hunters across 11 African communities. Researchers concluded that the literature relies on incomplete or second-hand accounts, which do not convincingly indicate that this cooperation widely or commonly occurs, if at all.

Interviews from three communities in Tanzania suggest something is happening. The most notable result came from members of the Hadzabe tribe. 61% of interviewees confirmed that they have seen this happening.

Yet skeptics point to the honey badger’s sensory limitations: their lackluster hearing and vision should make it difficult for them to follow a bird’s chattering call. While the jury is still out, it would not be unprecedented.

After all, other mustelids happily pass knowledge on to their offspring. We also know some are open to partnerships with other animals.

Sea Otters: Nature’s Tool Collectors

“In every curving beach, in every grain of sand, there is the story of the Earth.”

— Rachel Carson

The Haida people of the Pacific Northwest tell the story of Kousta, an otter who married a human woman and taught her people how to harvest shellfish. Kousta shared the secrets of which rocks worked best for cracking shells and showed her sustainable harvesting practices.

When humans killed him (because gratitude is a fleeting thing), his grieving widow took his pelt and threw it into the ocean. Where it touched the water, the first kelp forests sprang up to provide hiding places where otters could always find sanctuary. The Haida say this is why sea otters live among the kelp and why we must always harvest responsibly.

This story has a strong basis in reality. Pups, dependent on moms for 6-7 months, observe foraging and tool use from birth. Mothers show them how to crack shellfish and even provide practice stones.

Granted, orphan pups can learn independently, but maternal transmission boosts efficiency. Females, being smaller and having weaker bites, rely more on tools than males. Tool use spreads horizontally in groups too.

Otter see, otter do.

It’s Tool Time:

- Each otter has a favorite rock that they keep in a loose skin pocket under their armpit

- Mother otters teach pups which rocks work best for different types of shellfish

- They can crack 1,000 shellfish a day

- Some otters use bottles, cans, or other human debris as tools when rocks aren’t available

More Sea Otter Superpowers:

- They have the densest fur in the animal kingdom—up to 1 million hairs per square inch

- They hold hands while sleeping to avoid drifting apart (called “rafting”)

- A group of otters floating together is called a “raft,” but on land they’re called a “romp”

- They do somersaults while eating to wash food particles out of their fur

- Baby otters are so buoyant they can’t dive. They float like corks until they’re older

- By eating sea urchins, they save kelp forests from destruction

European Badgers: Subterranean Architects

“I’m a beast, I am, and a Badger what’s more. We don’t change. We hold on.”

– C. S. Lewis (was he a furry?)

In British folklore, badgers were called “brock” (from the Old English word meaning “grey”, which itself has older Celtic roots). Broch the Silver, a white badger from Welsh legend, lived for centuries in the mountains of Snowdonia.

Broch guided King Arthur’s knights through hidden mountain paths when they were lost in winter storms, and his silver-white coat glowed like a beacon. The Welsh believe that Broch still lives in the deepest setts (dens), still appearing to those who were truly lost and in desperate need. Killing a white badger is considered the worst luck imaginable; it begets a curse that lasts seven generations.

European badgers (Meles meles) build homes that last centuries. These underground tunnel systems, called setts, get passed down through generations like family estates. Setts can house up to 35 badgers, with clans occupying multiple sites. They’re obsessively maintained; the bedding, made of grass and leaves, is regularly changed.

Badger Engineering Facts:

- Some setts contain miles of interconnected tunnels with multiple entrances (up to 50)

- The tunnels include nursery chambers, food storage areas, and “latrines”

- A single sett can house multiple families for over 100 years

- The largest recorded sett had 50 entrances and 310 yards of tunnels (one in Switzerland spanned 300m)

- Badgers can dig through frozen ground and solid clay. If that doesn’t sound impressive, try it yourself!

Weird Badger History:

- Badger hair makes the best shaving brushes because it holds water perfectly

- People used to believe badger fat could cure arthritis and joint pain

- The verb “badger” (to persistently bother someone) comes from badger-baiting, a cruel medieval sport. Unfortunately, according to The Badger Trust, this practice has not completely vanished.

American Badgers and Friends

“If everyone is moving forward together, then success takes care of itself.”

— Henry Ford

Unlike their British cousins, American badgers don’t look like tea sipping gentlemen. The Navajo tell the story of Coyote and Badger, who were once bitter rivals competing for the same prairie dog colonies.

One day, Prairie Dog tricked them both, collapsing a burrow on Coyote while Badger dug from the wrong direction. Both predators went home hungry and exhausted. The next morning, they met at the same prairie dog town, and instead of fighting, Coyote suggested: “You dig from below, I’ll chase from above.” Together they caught enough to feed both their families.

The Navajo say this is why coyotes and badgers are “cousins” who still hunt together. Trail cameras throughout the western U.S. have captured badgers burrowing while coyotes chase escapees. Recent footage shows pairs traveling through culverts and rock piles, even playing between hunts.

In contrast to the manorial setts of Europe, American badgers are solitary and nomadic. Of course, they can still burrow with the best of them, disappearing underground in moments. They often dig a new, narrow, temporary burrow every day to sleep unperturbed by wolves, mountain lions, and other large carnivores.

Despite sharing a name, the badgers we’ve covered aren’t closely related. They have evolved similar body plans (stocky, low to the ground) because they occupy similar ecological niches, not because they share an especially recent ancestor.

Wolverines: The Arctic’s Toughest Hombres

“Here was neither peace, nor rest, nor a moment’s safety. All was confusion and action, and every moment life and limb were in peril.”

— Jack London, The Call of the Wild

Wolverines (Gulo gulo) appear in mythology across the northern hemisphere as symbols of savage self-reliance.

Kuekuatsheu, the trickster wolverine in Inuit myth became jealous when a giant kept summer locked in a massive bag. While other animals cowered, Kuekuatsheu crept into the giant’s cave and gnawed through the bag, releasing summer. When the giant woke, Kuekuatsheu had to scatter pieces of summer across the tundra, hiding them in rocks and snow.

This is why summer only visits the Arctic briefly, why it’s scattered unevenly there, and why wolverines still obsessively cache food. Norse mythology associated them with berserkers, warriors who fought with supernatural fury. The Cree called them “ommeethatsees” (the evil ones) and believed their strength and bravery came from dark magic.

Wolverines live in some of the harshest conditions on Earth, so they’ve evolved to think big. Scarcity is their reality, so a single wolverine might roam across 300 square miles. Never ones to take the easy way out, wolverines don’t hibernate. They happily(?) scavenge and hunt in -40°F weather (which is also -40° celsius, the only temperature at which C and F are the same).

Wolverine Survival Stats:

- They can travel 15 miles per day through deep snow

- Their large and extendable paws are like built-in snowshoes

- They can detect carrion buried under 20 feet of snow

- Males can weigh up to 55 pounds but take down sheep, bison, and full-grown moose!

- They have special molars designed for crushing frozen bones (rotated 90 degrees for shearing)

Arctic Superpowers:

- Wolverine fur is so good at repelling frost that Inuit peoples still prefer it for parka hoods (hollow hairs trap air)

- They can survive temperatures as low as -40°F

- They’re excellent climbers and can scale near-vertical cliffs

- Mothers give birth in snow dens and nurse cubs through -30°F winters

Pine Martens: Forest Ninjas

“There is no repose like that of all the green deep woods.”

— John Muir

In Scottish Highland tradition, the creature known as the Cat Sìth was often not a cat at all, but a pine marten, a distinction lost on those who glimpsed it slipping through the forest. The Scots believed the Cat Sìth could steal the souls of the dying before they reached heaven, but it had one weakness: vanity.

Families would distract the creature by leaving out saucers of cream, which the Cat Sìth couldn’t resist. While it lapped up the offering, souls could escape to safety. This is why, even today, some Scottish households leave cream out for “the fairy cat.”

Pine martens (Martes martes) solved urban planning better than most cities. Their elevated highway system allows for fast travel through forest canopies.

Pine martens are one of the few predators that can consistently catch squirrels. They are even more adept at moving through the trees than these furry-tailed rodents. In some areas, they’re helping control invasive gray squirrels, though their effectiveness depends on forest connectivity. Their diet isn’t limited to small mammals; they readily eat berries, nuts, and honey depending on the season.

Appropriately for such successful arboreal hunters, a group of martens is called a “richness.”

Parkour Masters:

- They can leap 20 feet (up to 4 meters) between trees

- They run headfirst down tree trunks (like squirrels)

- They have semi-retractable claws for superior grip

- They can rotate their hind feet 180 degrees for better climbing

- Top speed through the trees: 15 mph

- They rarely spend more than 15% of their time on the ground

Forest Life Facts:

- They build multiple dens and rotate between them

- European stone martens are notorious for chewing car cables (especially BMW and Honda)

- They’re excellent swimmers despite living in trees

- They have a distinctive yellow “bib” patch on their chest

- Baby martens are called “kits” and can’t climb for their first 7 weeks

- They live 8-10 years in the wild, up to 18 in captivity

Weasels: Tiny Hypnotists

“Eagles may soar, but weasels don’t get sucked into jet engines.”

— Steven Wright or John Benfield, probably Steven Wright

Weasels appear in folklore around the world as cunning tricksters and shapeshifters. In Japanese legend, the Kamaitachi (sickle weasels) were three weasel spirits that rode on whirlwinds and dust devils.

The first weasel knocked them down, the second cut them with invisible blades, and the third applied a salve so the wounds wouldn’t hurt right away. Farmers would walk through winter fields and suddenly discover cuts on their legs with no memory of being injured.

The Japanese blamed the Kamaitachi, though we now know such wounds were caused by frostbite or sharp ice crystals. Still, anyone who has watched a weasel move might believe they really can ride the wind.

“Weasel War (Dance), what is it good for?

Possibly something.”

– Edwin Starr, if he was a mustelid

When a weasel encounters a rabbit ten times its size, it starts jumping, spinning, and gyrating in seemingly random patterns. One theory is that this confuses or disorients prey, and rabbits have reportedly “died of fright” from the display. But weasels also dance when no prey is nearby, suggesting it might be a way to play or blow off steam (as well as a way to cleanly slaughter rabbits).

Weasel Size Records:

- Least weasels are the world’s smallest carnivorans (2 ounces)

- They can kill rabbits that weigh 10 times more than they do

- Their heart rate can reach 400 beats per minute during hunts

- They need to eat 40% of their body weight daily

- They can fit through any hole larger than their skull

Weasel Superpowers:

- Some species turn white in winter (stoats/ermines)

- They have a “killing bite” that targets the base of the skull

- They can take down prey in complete darkness, relying on their ears and noses

- Baby weasels are born deaf, blind, and hairless

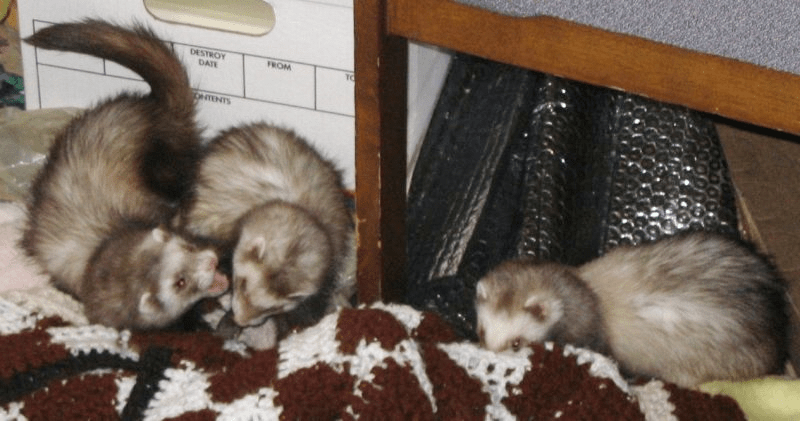

Ferrets: Professional Sleepers

“Do come back and draw the ferrets, they are the most lovely noble darlings in the world.”

— D. H. Lawrence

Ferrets have been our companions for over 2,000 years, and folklore reflects the length of this relationship. In medieval England and Wales, they gained a peculiar reputation as treasure hunters.

It was widely believed that ferrets could smell buried gold and silver through solid earth, which is why nobles would bring them along to explore Roman ruins and abandoned castles. When a ferret started digging frantically or acting excited, earnest excavation would begin.

While there’s no evidence to suggest that ferrets are attuned to the scent of precious metals (or, if they can, especially care for the smell), they are drawn to small, dark spaces where rodents nest. Rodents enjoy collecting shiny objects. So, occasionally following a ferret would lead to coins and jewelry pack rats had stashed away. These scores put “ferret out” into the English lexicon.

Domestic ferrets (Mustela furo) sleep 18-20 hours a day. They slumber so deeply that you can pick them up without waking them. This is an energy conservation strategy inherited from wild polecat ancestors, who sleep 14-18 hours to recharge after bursts of activity. Known as “dead sleep,” they become limp and unresponsive. They dream vividly, twitching as if they are running.

Ferret Fun Facts:

- A group of ferrets is called a “business”

- They can live 7-10 years as pets

- They’re born deaf and blind, opening their eyes at 5-6 weeks

- Baby ferrets are called “kits”

- They do a “happy dance” similar to the weasel war dance

- They’re excellent swimmers despite preferring to stay dry

- They can be litter trained like cats

Working Ferrets:

- They were used for hunting rabbits for over 2,000 years (ferreting was introduced by Normans in 11th century England)

- They help run cables through tight spaces during construction projects

- Some airports use them to run wires through walls

- They have an instinct to explore every tunnel and hole they find

- They’re still used for rabbit control in some countries

Illustration by Julius Csotonyi, courtesy of Applesauce Press. Florida Museum manager brings prehistoric mammals to life in new book

Bonus: Prehistoric Terror

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

— William Faulkner

Meet Ekorus ekakeran, the “running badger” of late Miocene Kenya, who lived 5.8 to 6 million years ago.

While its living cousins are built for digging and wrestling, Ekorus had long, slender legs designed for pursuit hunting across open grasslands. Weighing 40-60 pounds with massive bone-crushing carnassial teeth, Ekorus was probably an apex predator, relentlessly stalking its meals across the African savanna.

Ekorus is a reminder that the mustelid body plan, like everything, is mutable. Before big cats dominated Africa’s landscape, mustelids were experimenting with the cursorial (running) predator niche.

Though Ekorus disappeared as larger carnivorans entered the picture, its legacy lives on, from the tiniest Least Weasels to tank-like wolverines. The animal with the finest plumage, sharpest brain, or strongest bite does not necessarily win in the Darwinian sense.

Survival, immediately and broadly, comes down to being clever enough to find your niche, adaptable enough to find another, and tenacious enough to defend it (and yourself) to the death.

This is what mustelids teach us.

Mustelid Conservation Organizations

Honey Badger (Mellivora capensis)

- Niassa Carnivore Project (NCP): Focuses on research and human-wildlife conflict mitigation for carnivores, including honey badgers, in Mozambique.

- Link: https://niassalion.org/

- African Wildlife Foundation (AWF): Works to reduce retaliatory killings of honey badgers near human settlements through community programs and predator-proof enclosures.

Sea Otters

- Sea Otter Savvy: Dedicated to community awareness and education to minimize human disturbance to sea otters along the US Pacific Coast, emphasizing responsible viewing.

- IUCN Otter Specialist Group (OSG): The global scientific authority responsible for assessing the conservation status and promoting the protection of all 13 otter species.

European Badgers (Meles meles)

- The Badger Trust (UK): The leading national voice for badgers in England and Wales. It campaigns against badger culling and works to combat wildlife crime.

- The Wildlife Trusts (UK): A partnership of UK charities involved in grassroots action, including community-led badger vaccination programs and non-lethal conflict resolution.

Wolverines (Gulo gulo)

- Conservation Northwest (US): Advocates for US Endangered Species Act protections and conducts research on wolverine recovery in the mountainous Pacific Northwest.

- Rocky Mountain Wild (US): A key organization working to advance the planned reintroduction and recovery of wolverines in the Southern Rocky Mountains (e.g., Colorado).

Pine Martens (Martes martes)

- Vincent Wildlife Trust (VWT): Has led the recovery and reintroduction of the pine marten to parts of the UK, such as Wales and England, through their “Martens on the Move” project.

Weasels & Ferrets (Mustela Genus)

- National Black-Footed Ferret Conservation Center (USFWS): Manages the US-led captive breeding and reintroduction program for the critically endangered Black-Footed Ferret, a major success story for the genus.

- Mustelid Rescue UK: A specialized organization focusing on the rescue, rehabilitation, and release of smaller mustelids, specifically wild stoats and weasels.

References and Suggested Resources

Balunek, E. (2025, March 17). Fascinating trail cam videos show coyotes and badgers hunting prairie dogs together. Outdoor Life. https://www.outdoorlife.com/hunting/video-coyote-badger-hunt-together/

BBC. (2014, April 17). BBC Two – Natural World, 2014-2015, Honey Badgers: Masters of Mayhem. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0418x7x

Becker, E. F., Lee, D. C., & Mata, J. (2007). Bite force and cranial bone strain in four species of lizards. Journal of Experimental Biology, 210(7), 1190–1203. (Note: Wolverine bite force data referenced in secondary sources; direct access via academic databases recommended for full text.)

Cram, D. L., Van der Wal, J. E. M., Wood, B. M., Spottiswoode, C. N., & Flower, T. P. (2017). Mitogenomes and relatedness do not predict frequency of tool-use by sea otters. Ecology and Evolution, 7(8), 2550–2557. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2889

Goszczyński, J., & Wójtowicz, I. (2003). Patterns of sett use and territory of the European badger (Meles meles) in the Białowieża Forest. Acta Theriologica, 48(4), 483–492.

Hewson, R., & Healing, T. (1977). The “stoat” rabbit syndrome: Some preliminary observations. Journal of Zoology, 182(3), 417–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1977.tb01186.x

Kruuk, H. (1989). The social badger: Ecology and behaviour of Meles meles. Oxford University Press. (Original source for Woodchester Park sett observations.)

Owens, C. (1969). The domestication of the ferret. In P. J. Ucko & G. W. Dimbleby (Eds.), The domestication and exploitation of plants and animals (pp. 299–304). Aldine Publishing Company.

Poole, T. B. (1972). Some behavioural differences between the European polecat, Mustela putorius, the ferret, M. furo, and their hybrids. Journal of Zoology, 166(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1972.tb01060.x

Roper, T. J. (1992). Badger Meles meles setts—architecture, internal environment and function. Mammal Review, 22(1), 13–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2907.1992.tb01117.x

Sheehy, E., Sutherland, C., O’Neill, D., & O’Meara, C. (2018). The enemy of my enemy is my friend: Native pine marten recovery reverses the decline of the red squirrel by suppressing grey squirrel populations. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1872), 20172603. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.2603

Sheehy, E., & Lawton, J. H. (2014). Population crash of an invasive species following the recovery of a native predator: The case of the American grey squirrel and the European pine marten in Ireland. Biodiversity and Conservation, 23(5), 753–761. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-014-0656-7

Stanton, L. A., Sullivan, M. S., & Fazio, J. M. (2018). A standardized ethogram for the felidae: A tool for behavioral researchers. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 203, 23–32. (Adapted for mustelid behaviors; see related studies on war dance.)

Van der Wal, J. E. M., Wood, B. M., Camacho, J. A., Craige, C. M., Cram, D. L., Flower, T. P., & Spottiswoode, C. N. (2023). Do honey badgers and greater honeyguide birds cooperate to access bees’ nests? Ecological evidence and honey-hunter accounts. Journal of Zoology, 320(3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/jzo.13093

Leave a comment